Hardly anyone today knows anything about the “Spanish flu” of 1918-1920 and the “Asian flu” of 1957. However, since knowledge about past pandemics would be very valuable for future health risks, researchers at UZH and ZHAW want to close this memory gap.

Author: Louis Schäfer

“All events that lead to the gathering of large numbers of people in the same place or in the same room” will be banned by decision of the Zurich cantonal government on 25 July. This affects public gatherings, church services and festivities of all kinds. The Bishop of Chur complains to the federal government, innkeepers to the cantonal government. Professional organisations go on strike.

However, the year we are in is not 2020 and the pathogen is not called COVID-19: the “Spanish flu” spread across Europe in 1918. In the months of June and July alone, at least 5,000 people in Zurich contracted the feverish disease. 39 people lost their lives. After the measures were relaxed again in August, a second wave in autumn caused at least 75,000 illnesses and 140 deaths.

Parallels can easily be drawn with the coronavirus pandemic. In both cases, it seems that the risk of a second wave was underestimated.

Switzerland’s disaster memory gap

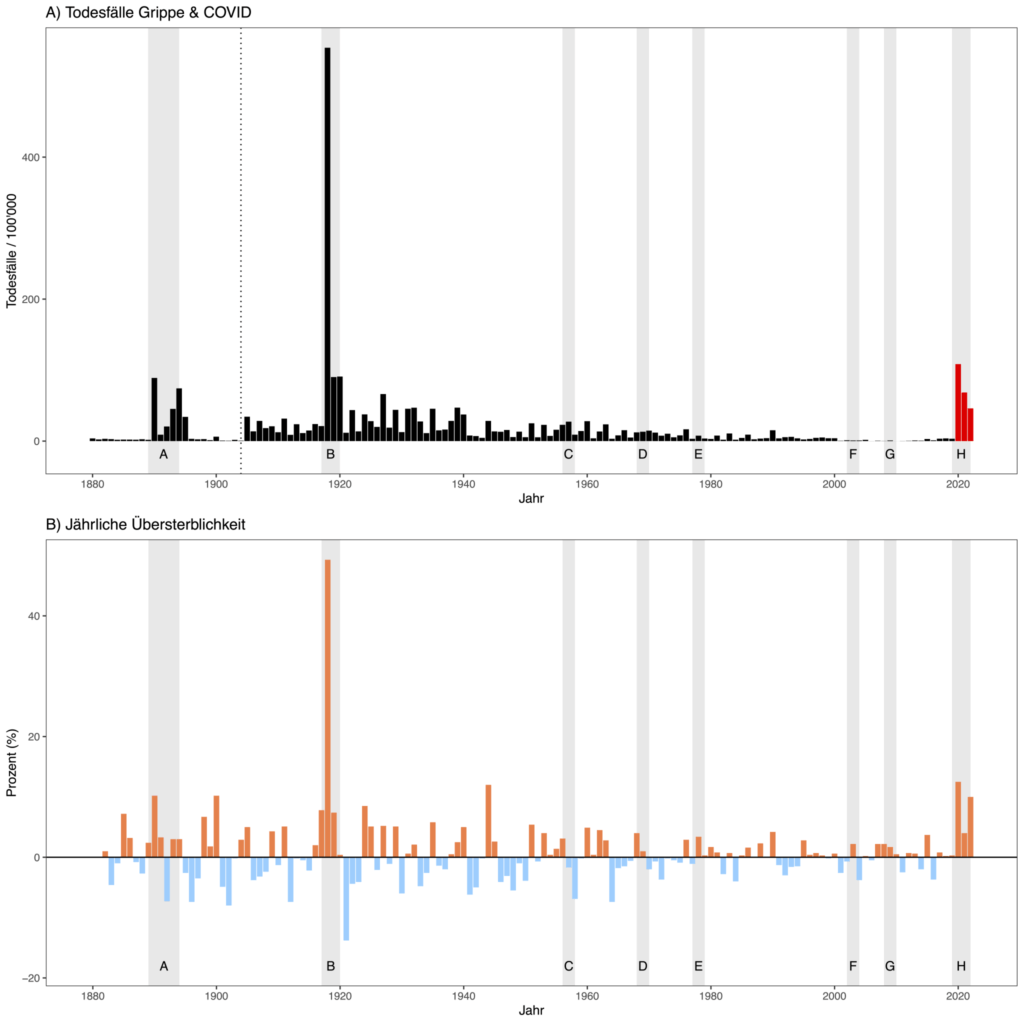

In Switzerland, the “Spanish flu” is still regarded as the worst demographic disaster of the 20th century. After it, no other influenza virus caused such a high mortality rate: the “Asian flu” (1957), the “Hong Kong flu” (1968) and the “Russian flu” (1977) were relatively mild. The same applies to “Sars” (2003) and “Swine flu (2009)”.

“As Switzerland has been spared serious pandemics since 1920, the authorities and population have forgotten how to deal with health risks,” says Kaspar Staub from the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine (UZH). He attests that Switzerland has a disaster memory gap. “We want to fill this gap by analysing past pandemics, making data available and making it accessible to the general public.”

He and researchers from the UZH and ZHAW have already tackled this task in the LEAD project, funded by the DIZH. They digitised data on mortality during various pandemics in Switzerland and made it publicly available on their project website. This data was also used to write the first data stories that clearly explain the historical pandemics.

A bridge between research and politics

In the follow-up project Bridging the gap, the research findings are now to be communicated to politicians, authorities and other relevant stakeholders. The science communication project started in September 2023 and is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). Data stories also play an important role this time.

“We want to supplement the data stories with statements from contemporary witnesses or their descendants,” says Wibke Weber from the IAM (ZHAW). The first step is to find interview partners who can tell us something about the “Spanish flu” and “Asian flu” (see call at the end). “By linking data and interview statements, the history of the pandemic can be made even more vivid.”

Another focus of the project concerns workshops at which the research findings are to be discussed with stakeholders from the authorities and healthcare system. “The aim is to bring the findings from the research to the people who make and implement important decisions in a health crisis,” says Kaspar Staub. “In addition to the workshops, we are also planning a larger public event, ideally at the Tonhalle Zurich.”

The venue was not chosen at random: In 1918, the Tonhalle was converted into an emergency hospital during the “Spanish flu”, when hospitals reached the limits of their capacity (see cover photo).

We are looking for contemporary witnesses

To find out more about historical pandemics, we are looking for contemporary witnesses or their descendants who can tell us something about the “Spanish flu” (1918-1920) and/or “Asian flu” (1957). We are planning interviews that will be recorded as videos or audio recordings and published on our website with the consent of the interviewees. Information from family diaries, stories or old letters is also welcome.

Get in touch and help us close the memory gap on past pandemics.

Contact: PD Dr. Kaspar Staub, kaspar.staub@iem.uzh.ch, +41 44 635 05 13

Further information: www.leaddata.ch

This article was published on 4.1.24 on Language matters, a blog of the ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences.